Found at www.heritage.nf.ca

Sinking of the Caribou

|

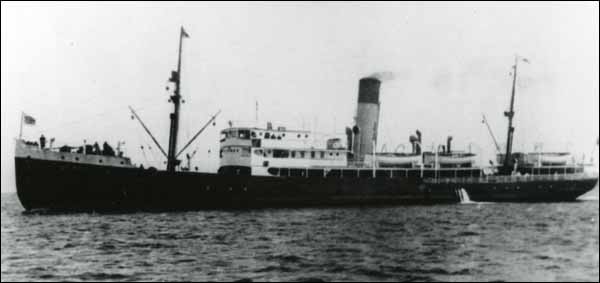

| SS Caribou, ca. 1920s - 1940s |

Photographer unknown. Reproduced by permission of Archives and Special Collections (Coll. 115 16.07.002), Queen Elizabeth II Library, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John's, NL.

U-69 and the Sinking of the SS Carolus

U-69, under the command of Kapitän-Leutnant Ulrich Gräf, entered the Gulf of St. Lawrence through the Cabot Strait on September 30, 1942. Finding no targets, he cruised up the St. Lawrence River and on the night of 8/9 October sighted the seven-ship, Labrador to Quebec convoy, NL-9. Despite the presence of three escorting corvettes, Gräf sank the 2245-ton steamship SS Carolus with the loss of 12 of her crew. This sinking, a mere 275 kilometres from Quebec City, caused an uproar in both Quebec and Ottawa. However, it would be nothing compared to the distress caused by the sinking of the Caribou a few nights later.October 13, 1942

The Sydney to Port aux Basques ferry SS Caribou left Sydney at approximately 9:30 p.m., on October 13, 1942. On board were 73 civilians, including 11 children, and 118 military personnel, plus a crew of 46. Just before departure, the Caribou’s master, Captain Benjamin Tavenor, ordered all passengers on deck to familiarize themselves with the lifeboat stations. Both he and his crew knew of the danger of U-boat attack – on the previous trip, the Caribou’s escort had attacked a contact, but without success. This might have been U-106, which had attacked a Sydney to Corner Brook convoy nine hours later.

Escorting the Caribou on this trip was the RCN minesweeper, HMCS Grandmere. According to her log, the night was very dark with no moon. Grandmere’s skipper, Lt. James Cuthbert, was unhappy about both the amount of smoke the Caribou was making and his screening position off the Caribou’s stern, which was in accordance with British naval procedures for a single escort. Cuthbert believed the best place for Grandmere to be was in front of the Caribou, not behind, as Western Approaches Convoy Instructions advised. He felt he would be better able to detect the sound of a lurking U-boat if he had a clear field in front to probe. He was correct, for in Caribou’s path lay the U-69.

The Attack

Gräf had actually been searching for a three-ship grain convoy heading for Montreal when at 3:21 a.m. he spotted the Caribou “belching heavy smoke” about 60 kilometres off the coast of Newfoundland. He misidentified the 2222-ton Rotterdam-built Caribou and the 670-ton Grandmere as a 6500-ton passenger freighter and a “two-stack destroyer.” At 3:40 a.m., according to Grandmere’s log, a lone torpedo hit the Caribou on her starboard side. Pandemonium ensued as passengers, thrown from their bunks by the explosion rushed topside to the lifeboat stations. For some reason, several families had been accommodated in separate cabins and now sought each other in the confusion. In addition, several lifeboats and rafts had either been destroyed in the explosion or could not be launched. As a result, many passengers were forced to jump overboard into the cold water.

Gräf had actually been searching for a three-ship grain convoy heading for Montreal when at 3:21 a.m. he spotted the Caribou “belching heavy smoke” about 60 kilometres off the coast of Newfoundland. He misidentified the 2222-ton Rotterdam-built Caribou and the 670-ton Grandmere as a 6500-ton passenger freighter and a “two-stack destroyer.” At 3:40 a.m., according to Grandmere’s log, a lone torpedo hit the Caribou on her starboard side. Pandemonium ensued as passengers, thrown from their bunks by the explosion rushed topside to the lifeboat stations. For some reason, several families had been accommodated in separate cabins and now sought each other in the confusion. In addition, several lifeboats and rafts had either been destroyed in the explosion or could not be launched. As a result, many passengers were forced to jump overboard into the cold water.

Assistance from the HMCS Grandmere

Meanwhile, Grandmere had spotted U-69 in the dark and turned to ram. Gräf, still under the impression he was facing a “destroyer” rather than a minesweeper, crash dived. As Grandmere passed over the swirl left by the submerged submarine, Lt. Cuthbert fired a diamond pattern of six depth charges. Gräf, meanwhile, headed for the sounds of the sinking Caribou, knowing that the survivors left floating on the surface would inhibit Grandmere from launching another attack. However, U-69’s manoeuvre went unnoticed by Grandmere and Cuthbert dropped another pattern of three charges set for 500 feet. Gräf fired a Bold, an asdic decoy, and slowly left the area.

Survivors

At 6:30 a.m. Grandmere gave up the hunt and started to pick up survivors. They were too few. Of the 237 people aboard the Caribou when she left North Sydney, 136 had perished. Fifty-seven were military personnel and 49 were civilians. Fifteen-month-old Leonard Shiers of Halifax was the only one of 11 children to survive the sinking. Of the 46-man crew, mostly Newfoundlanders, only 15 remained. Five families suffered particularly heavy losses: the Tappers (5 dead), the Toppers (4), the Allens (3), the Tavernors (the captain and his two sons), and the Skinners (3). The press truthfully reported that “Many Families [were] Wiped Out.”

Survivors of the SS Caribou, 14 October 1942

Unidentified survivors of the SS Caribou, which sank off the coast of Newfoundland on 14 October 1942 after being torpedoed by a German submarine. Of the 237 people on board, only 101 survived.

Photographer unknown. Reproduced by permission of Archives and Special Collections (Coll. 115 16.07.034), Queen Elizabeth II Library, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John's, NL.

News of the Attack Reaches the Island

News of the sinking sparked much outrage as victims’ friends and families, and the populace at large, condemned the Nazis for targeting a passenger ferry. An editorialist with The Royalist newspaper in St. John’s wrote that the sinking “was such a useless crime from the point of view of warfare. It will have no effect upon the course of the war except to steel our resolve that the Nazi blot on humanity must be eliminated from our world.” As bodies were recovered, the burials started. The Channel/Port aux Basques area was the worst hit as many crew members of the Caribou were local men. A funeral on October 18 for six victims was attended by hundreds of mourners, and a procession that followed the bodies to the grave sites reportedly measured two kilometres long.

The Burgeo took over the Caribou’s former route after the sinking, but eliminated night time sailings. To further reduce any possibility of attack, the Canadian navy ordered the ferry’s escort to navigate a zig-zag path in front of the vessel rather than follow from behind.

The Attack on the Rose Castle

The U-69, meanwhile, remained hidden in Newfoundland waters, and on October 20, attacked the ore carrier Rose Castle traveling to Bell Island from Sydney. This time the torpedo did not explode and the vessel escaped unharmed. The U-boat, out of torpedoes, headed for home and was eventually sunk the next February by the British destroyer HMS Viscount while attacking a convoy east of Newfoundland. All 46 of the U-69’s crew were killed in the attack.

The Strickland Story

The following narrative was written by a survivor of the Sydney to Port aux Basques passenger ferry SS Caribou, which sunk in the early hours of 14 October 1942 after being hit by a German torpedo. The text originally appeared in H. Thornhill’s It Happened in October: The Tragic Sinking of the SS Caribou.THE TALE OF MR. WILLIAM STRICKLAND and the loss of his wife and two children, Hobby and Nora, who were drowned on the S.S. Caribou.

"We sailed from North Sydney pier around 9 o’clock in the night. With me was my wife and two children. It was a very pleasant night at sea with a starlight sky. We occupied room No. 23 and soon after leaving my wife and children retired comfortably for the night and were soon fast asleep. I decided that I too would turn in.

I slept soundly until late in the morning which [sic] I awoke and got out of my berth. Realizing we were getting near Port Aux Basques, I was going to put on my shoes when I was shocked by a terrific explosion. I said to my wife, Gertie, “My God, we are torpedoed!” and then I told her to take the baby while I picked up Hobby, our eldest child. I also caught hold of my two life belts and opening the door, I made an effort to get on deck but the lights went out and everything was in pitch darkness except for a tiny dim light near the saloon.

We made our way for the starboard side and on arriving there we found a boat with about four men in it. Taking my child Hobby, I tossed her down aboard of the boat where my wife and baby were. As I began to get down myself, the life-boat capsized and I heard my wife cry out, “Hobby is gone.”

By that time, water was pouring over the deck of the ship and she was sinking fast. I cried out to someone to take my baby while I try and get up myself which they did and I finally managed to climb in myself. My wife, too managed to reach top deck and also another lady. There was nothing in sight available to get into. All I could hear was the cries and screams for help as the passengers seemed to be a terrible state of mind.

My wife screamed for her baby then grasped my hand and said, “Bill, we will go together.” By then, the water was to our knees and was still rising. A sea broke over us and we were separated from one another. From that moment, I never saw my wife again. The two lifebelts that I tried so hard to hold fast to were lost when I was trying to save my child.

As far as I can judge, I was caught in the suction of the ship and could not break clear. I went round and round with the current before I was able to break clear. I caught hold of a piece of debris about 4 feet long and had to let go of it again.

I went under water again and took in a considerable amount of water. It was a matter of life and death and a bitter struggle before I reached the surface again. When I did, I glanced ahead of me and I saw an object on the water and immediately began to swim toward it. It was a raft. I was the only one on it until about 15 minutes later when I caught sight of a woman swimming toward the same raft. I helped her on board and then she burst out in tears as she told me that her baby was lost. I tried to comfort her as I told her how I had lost my wife and two children.

After this five more survivors made their appearance, 4 men and a girl. We were on the lookout for the corvette and also tried to see if we could rescue any more people from the perils of the sea.

The girl we rescued was the first to see the rescue ship appearing in the distance. We were sitting with our feet in water for about 4 and one-half hours and were pretty cold when the rescue ship picked us up. We were brought to North Sydney.

Whoever may be privileged to read this tale can imagine what it means to be blasted from a cosy state room to a cold, icy water at 3 a.m. in the morning and lose all that memories hold dear."

(Signed)

Wm. Strickland,

North Sydney.

Native of Rose Blanche,

Newfoundland.

Click HERE for details of 136 people who were on board.

No comments:

Post a Comment