Wednesday, April 24, 2013

Monday, April 22, 2013

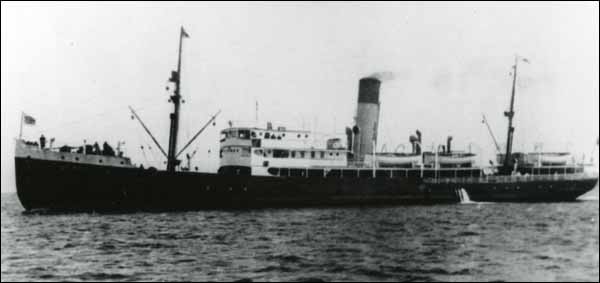

Caribou ~ 14 October 1942

Found at www.heritage.nf.ca

Sinking of the Caribou

|

| SS Caribou, ca. 1920s - 1940s |

Photographer unknown. Reproduced by permission of Archives and Special Collections (Coll. 115 16.07.002), Queen Elizabeth II Library, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John's, NL.

U-69 and the Sinking of the SS Carolus

U-69, under the command of Kapitän-Leutnant Ulrich Gräf, entered the Gulf of St. Lawrence through the Cabot Strait on September 30, 1942. Finding no targets, he cruised up the St. Lawrence River and on the night of 8/9 October sighted the seven-ship, Labrador to Quebec convoy, NL-9. Despite the presence of three escorting corvettes, Gräf sank the 2245-ton steamship SS Carolus with the loss of 12 of her crew. This sinking, a mere 275 kilometres from Quebec City, caused an uproar in both Quebec and Ottawa. However, it would be nothing compared to the distress caused by the sinking of the Caribou a few nights later.October 13, 1942

The Sydney to Port aux Basques ferry SS Caribou left Sydney at approximately 9:30 p.m., on October 13, 1942. On board were 73 civilians, including 11 children, and 118 military personnel, plus a crew of 46. Just before departure, the Caribou’s master, Captain Benjamin Tavenor, ordered all passengers on deck to familiarize themselves with the lifeboat stations. Both he and his crew knew of the danger of U-boat attack – on the previous trip, the Caribou’s escort had attacked a contact, but without success. This might have been U-106, which had attacked a Sydney to Corner Brook convoy nine hours later.

Escorting the Caribou on this trip was the RCN minesweeper, HMCS Grandmere. According to her log, the night was very dark with no moon. Grandmere’s skipper, Lt. James Cuthbert, was unhappy about both the amount of smoke the Caribou was making and his screening position off the Caribou’s stern, which was in accordance with British naval procedures for a single escort. Cuthbert believed the best place for Grandmere to be was in front of the Caribou, not behind, as Western Approaches Convoy Instructions advised. He felt he would be better able to detect the sound of a lurking U-boat if he had a clear field in front to probe. He was correct, for in Caribou’s path lay the U-69.

The Attack

Gräf had actually been searching for a three-ship grain convoy heading for Montreal when at 3:21 a.m. he spotted the Caribou “belching heavy smoke” about 60 kilometres off the coast of Newfoundland. He misidentified the 2222-ton Rotterdam-built Caribou and the 670-ton Grandmere as a 6500-ton passenger freighter and a “two-stack destroyer.” At 3:40 a.m., according to Grandmere’s log, a lone torpedo hit the Caribou on her starboard side. Pandemonium ensued as passengers, thrown from their bunks by the explosion rushed topside to the lifeboat stations. For some reason, several families had been accommodated in separate cabins and now sought each other in the confusion. In addition, several lifeboats and rafts had either been destroyed in the explosion or could not be launched. As a result, many passengers were forced to jump overboard into the cold water.

Gräf had actually been searching for a three-ship grain convoy heading for Montreal when at 3:21 a.m. he spotted the Caribou “belching heavy smoke” about 60 kilometres off the coast of Newfoundland. He misidentified the 2222-ton Rotterdam-built Caribou and the 670-ton Grandmere as a 6500-ton passenger freighter and a “two-stack destroyer.” At 3:40 a.m., according to Grandmere’s log, a lone torpedo hit the Caribou on her starboard side. Pandemonium ensued as passengers, thrown from their bunks by the explosion rushed topside to the lifeboat stations. For some reason, several families had been accommodated in separate cabins and now sought each other in the confusion. In addition, several lifeboats and rafts had either been destroyed in the explosion or could not be launched. As a result, many passengers were forced to jump overboard into the cold water.

Assistance from the HMCS Grandmere

Meanwhile, Grandmere had spotted U-69 in the dark and turned to ram. Gräf, still under the impression he was facing a “destroyer” rather than a minesweeper, crash dived. As Grandmere passed over the swirl left by the submerged submarine, Lt. Cuthbert fired a diamond pattern of six depth charges. Gräf, meanwhile, headed for the sounds of the sinking Caribou, knowing that the survivors left floating on the surface would inhibit Grandmere from launching another attack. However, U-69’s manoeuvre went unnoticed by Grandmere and Cuthbert dropped another pattern of three charges set for 500 feet. Gräf fired a Bold, an asdic decoy, and slowly left the area.

Survivors

At 6:30 a.m. Grandmere gave up the hunt and started to pick up survivors. They were too few. Of the 237 people aboard the Caribou when she left North Sydney, 136 had perished. Fifty-seven were military personnel and 49 were civilians. Fifteen-month-old Leonard Shiers of Halifax was the only one of 11 children to survive the sinking. Of the 46-man crew, mostly Newfoundlanders, only 15 remained. Five families suffered particularly heavy losses: the Tappers (5 dead), the Toppers (4), the Allens (3), the Tavernors (the captain and his two sons), and the Skinners (3). The press truthfully reported that “Many Families [were] Wiped Out.”

Survivors of the SS Caribou, 14 October 1942

Unidentified survivors of the SS Caribou, which sank off the coast of Newfoundland on 14 October 1942 after being torpedoed by a German submarine. Of the 237 people on board, only 101 survived.

Photographer unknown. Reproduced by permission of Archives and Special Collections (Coll. 115 16.07.034), Queen Elizabeth II Library, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John's, NL.

News of the Attack Reaches the Island

News of the sinking sparked much outrage as victims’ friends and families, and the populace at large, condemned the Nazis for targeting a passenger ferry. An editorialist with The Royalist newspaper in St. John’s wrote that the sinking “was such a useless crime from the point of view of warfare. It will have no effect upon the course of the war except to steel our resolve that the Nazi blot on humanity must be eliminated from our world.” As bodies were recovered, the burials started. The Channel/Port aux Basques area was the worst hit as many crew members of the Caribou were local men. A funeral on October 18 for six victims was attended by hundreds of mourners, and a procession that followed the bodies to the grave sites reportedly measured two kilometres long.

The Burgeo took over the Caribou’s former route after the sinking, but eliminated night time sailings. To further reduce any possibility of attack, the Canadian navy ordered the ferry’s escort to navigate a zig-zag path in front of the vessel rather than follow from behind.

The Attack on the Rose Castle

The U-69, meanwhile, remained hidden in Newfoundland waters, and on October 20, attacked the ore carrier Rose Castle traveling to Bell Island from Sydney. This time the torpedo did not explode and the vessel escaped unharmed. The U-boat, out of torpedoes, headed for home and was eventually sunk the next February by the British destroyer HMS Viscount while attacking a convoy east of Newfoundland. All 46 of the U-69’s crew were killed in the attack.

The Strickland Story

The following narrative was written by a survivor of the Sydney to Port aux Basques passenger ferry SS Caribou, which sunk in the early hours of 14 October 1942 after being hit by a German torpedo. The text originally appeared in H. Thornhill’s It Happened in October: The Tragic Sinking of the SS Caribou.THE TALE OF MR. WILLIAM STRICKLAND and the loss of his wife and two children, Hobby and Nora, who were drowned on the S.S. Caribou.

"We sailed from North Sydney pier around 9 o’clock in the night. With me was my wife and two children. It was a very pleasant night at sea with a starlight sky. We occupied room No. 23 and soon after leaving my wife and children retired comfortably for the night and were soon fast asleep. I decided that I too would turn in.

I slept soundly until late in the morning which [sic] I awoke and got out of my berth. Realizing we were getting near Port Aux Basques, I was going to put on my shoes when I was shocked by a terrific explosion. I said to my wife, Gertie, “My God, we are torpedoed!” and then I told her to take the baby while I picked up Hobby, our eldest child. I also caught hold of my two life belts and opening the door, I made an effort to get on deck but the lights went out and everything was in pitch darkness except for a tiny dim light near the saloon.

We made our way for the starboard side and on arriving there we found a boat with about four men in it. Taking my child Hobby, I tossed her down aboard of the boat where my wife and baby were. As I began to get down myself, the life-boat capsized and I heard my wife cry out, “Hobby is gone.”

By that time, water was pouring over the deck of the ship and she was sinking fast. I cried out to someone to take my baby while I try and get up myself which they did and I finally managed to climb in myself. My wife, too managed to reach top deck and also another lady. There was nothing in sight available to get into. All I could hear was the cries and screams for help as the passengers seemed to be a terrible state of mind.

My wife screamed for her baby then grasped my hand and said, “Bill, we will go together.” By then, the water was to our knees and was still rising. A sea broke over us and we were separated from one another. From that moment, I never saw my wife again. The two lifebelts that I tried so hard to hold fast to were lost when I was trying to save my child.

As far as I can judge, I was caught in the suction of the ship and could not break clear. I went round and round with the current before I was able to break clear. I caught hold of a piece of debris about 4 feet long and had to let go of it again.

I went under water again and took in a considerable amount of water. It was a matter of life and death and a bitter struggle before I reached the surface again. When I did, I glanced ahead of me and I saw an object on the water and immediately began to swim toward it. It was a raft. I was the only one on it until about 15 minutes later when I caught sight of a woman swimming toward the same raft. I helped her on board and then she burst out in tears as she told me that her baby was lost. I tried to comfort her as I told her how I had lost my wife and two children.

After this five more survivors made their appearance, 4 men and a girl. We were on the lookout for the corvette and also tried to see if we could rescue any more people from the perils of the sea.

The girl we rescued was the first to see the rescue ship appearing in the distance. We were sitting with our feet in water for about 4 and one-half hours and were pretty cold when the rescue ship picked us up. We were brought to North Sydney.

Whoever may be privileged to read this tale can imagine what it means to be blasted from a cosy state room to a cold, icy water at 3 a.m. in the morning and lose all that memories hold dear."

(Signed)

Wm. Strickland,

North Sydney.

Native of Rose Blanche,

Newfoundland.

Click HERE for details of 136 people who were on board.

Ceramic ~ 8 December 1942

Edited and expanded from www.ahoy.tk-jk.net

Ceramic had a long history, she had been built and delivered by Harland and Wolff Ltd of Belfast in 1913 for her then owners White Star Line Ltd. Her length: 655.1 feet, beam: 69.4 feet and draught: 43.8 feet, giving her a gross tonnage of 18,481 tons. Her speed, 15knots, powered by three triple expansion and low powered turbines all geared to a central shaft.

The SS Ceramic plied the UK/Australia route via the Cape of Good Hope. With her tall masts, she reportedly held the record for the highest masts that could still clear the Sydney Harbour Bridge. In 1914, with the declaration of WWI, she was requisitioned as a Trooper for the Australian Expeditionary Force.

Near misses by torpedoes.

Twice during WW1, the ship escaped being torpedoed, once in the Mediterranean in 1916, and a second time in 1917, in the English Channel.

Change of Ownership.

Cunard - White Star Ltd. was formed in 1934 to aid the Queen Mary project, and Shaw Saville and Albion acquired the Australian assets of the old White Star line, and these included Ceramic.

Reconstruction of the ship by her original builders.

In 1935, Harland and Wolff reconstructed this vessel, her new tonnage a shade heavier at 18,713 gross, and a slightly improved speed of 16 knots. The new design catered for 480 cabin class passengers, and her "Veranda Cafe" aft, dates from this rework.

WWII.

With the advent of WWII, the Ceramic once again donned Troopship colours, for service in that capacity out of Australia, but she still carried some passengers.

Collision.

On the 11th of August 1940 the ship was involved in a collision with SS Testbank, and was towed into Walwis Bay in SW Africa for temporary repairs.

1942.

On the 23rd of November 1942, Ceramic, under the command of Captain Elford, cleared the Mersey River at Liverpool, and set off for St. Helena, Durban, and Sydney. She had on board, 378 passengers, which included 12 children, 244 Naval/Military/Nursing personnel and 278 crew (in that number were 33 Australian seamen). In her holds were stowed 12,362 tons of general cargo and government stores.

That fateful day of the 7th of December 1942.

When steaming west of the Azores on the 7th of December 1942 the ship was sighted and then stalked by the German U-Boat U-515 (Captain Werner Henke). The weather was cold with rough seas. Henke struck with one torpedo about 8:00 p.m. Several minutes after this explosion, two more hits were made in the engine room.

The stricken ship stopped and darkness descended on board. 8 life boats, all crammed full, were lowered and got away from the sinking ship but she did not go down immediately. Just prior to midnight, two more torpedoes were released, to break the ship in two, and in another 10 seconds she was gone.

By now it was raining to make the life of the survivors even more miserable and the sea was very rough, with the life boats in danger of being swamped by the rising waves. By 8:00 a.m. the next morning, a Force 10 gale was blowing, and lifeboats were capsizing. Many of the survivors found themselves battling it out with huge seas, supported only by their life jackets.

About noon, the U-515 returned to the tragic scene and surfaced close to a group of survivors who thought rescue was at hand. Sadly no ... two German sailors threw a line to one man, Eric Monday of the Royal Engineers. He was hauled aboard to become a Prisoner of War and to be interrogated. He wound up in Stalag 8B in Upper Silesia, to remain imprisoned until his final release when WWII came to an end. Apparently U-Boat Command had ordered Henke to return to the scene of the sinking, in order to try and pick up the ship's captain to ascertain Ceramic's destination.

U-515 sailed away, leaving 655 of the ship's company to perish. Eric Monday her sole survivor.

Recording the names of those who perished in Ceramic.

All the Service personnel have their names recorded on the Brookwood War Memorial in Surrey England. The Civilian War Dead Register names all the civilian passengers. The Merchant Navy Personnel have their names recorded on the Tower Hill Memorial in London. The 33 Australian Seamen in Ceramic's crew are recorded on the Australian Merchant Seamen's Memorial in Canberra, Australian Capital Territory.

SS Ceramic, a victim of U-515 on the 7th. of December 1942

Ceramic when sailing under White Star colours

Near misses by torpedoes.

Twice during WW1, the ship escaped being torpedoed, once in the Mediterranean in 1916, and a second time in 1917, in the English Channel.

Change of Ownership.

Cunard - White Star Ltd. was formed in 1934 to aid the Queen Mary project, and Shaw Saville and Albion acquired the Australian assets of the old White Star line, and these included Ceramic.

Reconstruction of the ship by her original builders.

In 1935, Harland and Wolff reconstructed this vessel, her new tonnage a shade heavier at 18,713 gross, and a slightly improved speed of 16 knots. The new design catered for 480 cabin class passengers, and her "Veranda Cafe" aft, dates from this rework.

WWII.

With the advent of WWII, the Ceramic once again donned Troopship colours, for service in that capacity out of Australia, but she still carried some passengers.

Collision.

On the 11th of August 1940 the ship was involved in a collision with SS Testbank, and was towed into Walwis Bay in SW Africa for temporary repairs.

Ceramic on a cigarette card.

On the 23rd of November 1942, Ceramic, under the command of Captain Elford, cleared the Mersey River at Liverpool, and set off for St. Helena, Durban, and Sydney. She had on board, 378 passengers, which included 12 children, 244 Naval/Military/Nursing personnel and 278 crew (in that number were 33 Australian seamen). In her holds were stowed 12,362 tons of general cargo and government stores.

That fateful day of the 7th of December 1942.

(NOTE: In England, the loss of Ceramic is recorded as the 6th of December 1942. It's reporting this loss by English time rather than the local time obtaining at the time which made the sinking on the 7th of December 1942.)

When steaming west of the Azores on the 7th of December 1942 the ship was sighted and then stalked by the German U-Boat U-515 (Captain Werner Henke). The weather was cold with rough seas. Henke struck with one torpedo about 8:00 p.m. Several minutes after this explosion, two more hits were made in the engine room.

The stricken ship stopped and darkness descended on board. 8 life boats, all crammed full, were lowered and got away from the sinking ship but she did not go down immediately. Just prior to midnight, two more torpedoes were released, to break the ship in two, and in another 10 seconds she was gone.

By now it was raining to make the life of the survivors even more miserable and the sea was very rough, with the life boats in danger of being swamped by the rising waves. By 8:00 a.m. the next morning, a Force 10 gale was blowing, and lifeboats were capsizing. Many of the survivors found themselves battling it out with huge seas, supported only by their life jackets.

About noon, the U-515 returned to the tragic scene and surfaced close to a group of survivors who thought rescue was at hand. Sadly no ... two German sailors threw a line to one man, Eric Monday of the Royal Engineers. He was hauled aboard to become a Prisoner of War and to be interrogated. He wound up in Stalag 8B in Upper Silesia, to remain imprisoned until his final release when WWII came to an end. Apparently U-Boat Command had ordered Henke to return to the scene of the sinking, in order to try and pick up the ship's captain to ascertain Ceramic's destination.

U-515 sailed away, leaving 655 of the ship's company to perish. Eric Monday her sole survivor.

Fate of U-515 and her Captain.

In April 1944, American warships caught up with and sank U-515. Captain Werner Henke, who had already sunk 26 ships, was shot two months later trying to escape from a prison camp in Virginia, though from the way he calmly started to climb the fence in broad daylight in full view of the guards and refuses an order to stop suggests that he was committing suicide to avoid being tried as a war criminal over the Ceramic disaster. Royal Engineer Eric Monday, the only passenger rescued from the sinking, would survive the war in a German POW camp.

Read article published about Werner Henke on AHOY.

Recording the names of those who perished in Ceramic.

All the Service personnel have their names recorded on the Brookwood War Memorial in Surrey England. The Civilian War Dead Register names all the civilian passengers. The Merchant Navy Personnel have their names recorded on the Tower Hill Memorial in London. The 33 Australian Seamen in Ceramic's crew are recorded on the Australian Merchant Seamen's Memorial in Canberra, Australian Capital Territory.

Click HERE for details of 656 people who were on board.

Click HERE for more photos.

Friday, April 19, 2013

Fiume ~ 24 September 1942

The Fiume was a small Italian passenger steamer sunk by the Greek submarine Nereus on September 24, 1942 while sailing from Rhodes to Symi. The ship sank in less than 30 seconds, taking 214 of the 287 passengers and crew down with her. No further information has been found.

Saturday, April 13, 2013

Lady Hawkins ~ 19 January 1942

The RMS Lady Hawkins was a steam turbine ocean liner. She was one of a class of five sister ships popularly known as "Lady Boats" that Cammell Laird of Birkenhead, England built in 1928 and 1929 for the Canadian National Steamship Company (CNS). The five vessels were Royal Mail Ships that CN operated from Halifax, Nova Scotia and the Caribbean via Bermuda.

In January 1942 Lady Hawkins sailed from Montreal for Bermuda and the Caribbean. She called at Halifax and Boston, and by the time she left Boston she was carrying 2,908 tons of general cargo and 213 passengers as well as her complement of 107 officers, crew and DEMS gunners. At least 53 of her passengers were Royal Navy and RNVR personnel, and at least another 55 were civilians, including at least 15 from the British West Indies and four from the United States.

In January 1942 Lady Hawkins sailed from Montreal for Bermuda and the Caribbean. She called at Halifax and Boston, and by the time she left Boston she was carrying 2,908 tons of general cargo and 213 passengers as well as her complement of 107 officers, crew and DEMS gunners. At least 53 of her passengers were Royal Navy and RNVR personnel, and at least another 55 were civilians, including at least 15 from the British West Indies and four from the United States.

On the morning of January 19, 1942 the ship was sailing unescorted about 150 nautical miles off Cape Hatteras, taking a zigzag course to make her more difficult to hit, when at 0743 hrs U-66 commanded by Korvettenkapitän Robert-Richard Zapp hit her with two stern-launched torpedoes. The liner sank in about 30 minutes.

Three of her six lifeboats were damaged, but the other three were launched. One was commanded by her Chief Officer. It had capacity for 63 people but managed to embark 76 survivors. Its occupants could hear more people in the water, but could neither see them in the dark nor take them aboard the overcrowded boat if they had found them.

The boat had no radio transmitter and very limited rations of drinking water, ship's biscuit and condensed milk. It shipped water and needed constant baling, but it had a mast, sail and oars and Chief Officer Percy Kelly set a course west toward the U.S. Atlantic coast sea lanes and land.

Three of her six lifeboats were damaged, but the other three were launched. One was commanded by her Chief Officer. It had capacity for 63 people but managed to embark 76 survivors. Its occupants could hear more people in the water, but could neither see them in the dark nor take them aboard the overcrowded boat if they had found them.

The boat had no radio transmitter and very limited rations of drinking water, ship's biscuit and condensed milk. It shipped water and needed constant baling, but it had a mast, sail and oars and Chief Officer Percy Kelly set a course west toward the U.S. Atlantic coast sea lanes and land.

The boat was at sea for five days, in which time five of its occupants died. Then the survivors sighted the U.S. Army troop ship USAT Coamo and signaled her with a flashlight. Coamo 's Master misread the flashes as an enemy submarine preparing to attack, and was going to continue without stopping. It was only when the survivors shone the light on the boat's sail that he correctly understood their signal. Coamo rescued the boat's 71 surviving occupants, landing them at San Juan, Puerto Rico on January 28.

Of the three lifeboats launched, only Chief Officer Kelly's was found. Including the five who died in that boat, a total of 251 people from Lady Hawkins were lost. They were her Master Huntly Giffen, 85 of her crew, one DEMS gunner and 164 of her passengers, two of whom were Distressed British Seamen (i.e. survivors from previous sinkings). The 71 survivors whom Coamo rescued were Percy Kelly, 21 crew and 49 passengers.

Click HERE for details of 207 people who were on board.

Of the three lifeboats launched, only Chief Officer Kelly's was found. Including the five who died in that boat, a total of 251 people from Lady Hawkins were lost. They were her Master Huntly Giffen, 85 of her crew, one DEMS gunner and 164 of her passengers, two of whom were Distressed British Seamen (i.e. survivors from previous sinkings). The 71 survivors whom Coamo rescued were Percy Kelly, 21 crew and 49 passengers.

Click HERE for details of 207 people who were on board.

Sunday, April 7, 2013

Rooseboom ~ 1 March 1942

The SS Rooseboom was a 1,035 ton Dutch steam ship owned by Koninklijke Paketvaart-Maatschappij (KPM) or Royal Packet Navigation Co. of the Netherlands East Indies built in 1926 by Rijkee & Co of Rotterdam.

The lifeboat.

Walter Gardiner Gibson (a corporal from the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders is the only known witness of the events that would occur on the lifeboat over the next 26 days. His tale was told to the British authorities after the war but was first heard publicly in court in Edinburgh in 1949 in order to confirm that Major Angus Macdonald was dead so that his estate could be settled.

According to Gibson, in and around the lifeboat were an estimated 135 survivors, many with injuries, including Gibson himself who was in the lifeboat due to those injuries. Among the survivors were the Captain M.C.A. Boon and the senior surviving British officer Brigadier Archie Paris (who had commanded the 15th Indian Infantry Brigade during the Battle of Malaya). There were also two other Argyll officers aboard the Rooseboom; Major Angus Macdonald, second in command of the Argylls and Captain Mike Blackwood. These two officers were chiefly responsible for holding up a Japanese tank column during the Battle of Bukit Timah. Paris, MacDonald, Blackwood and number of the other military passengers were among a selected few of the most proven fighters chosen to be evacuated instead of being lost to a POW camp.

In February 1942 British Malaya and Singapore had surrendered to the Japanese Army. Over 100,000 British and Empire military personnel had become prisoners as well as thousands of civilians. A few thousand more were escaping to the nearby Netherlands East Indies and from there to Australia, Ceylon or India in any ship that could be found. Many of these ships were lost to Japanese attacks among the islands scattered around Sumatra and Java while attempting to escape. Rooseboom under Captain Marinus Cornelis Anthonie Boon, was taking around 500 passengers (mainly British military personnel and civilians) from Padang to Colombo in Ceylon.

On March 1, 1942 at 11:35 p.m. Rooseboom was steaming west of Sumatra when it was spotted by the Japanese submarine I-59 (which was later re designated I-159) under the command of Lieutenant Yoshimatsu and torpedoed. Rooseboom capsized and sank rapidly leaving one life boat (designed to hold 28) and 135 people in the water. 80 people were in the lifeboat and the rest clung to flotsam or floated in the sea. Two of these survivors were picked up 9 days later by the Dutch freighter Palopo. Until the end of the WWII they were assumed to be the only survivors.

On March 1, 1942 at 11:35 p.m. Rooseboom was steaming west of Sumatra when it was spotted by the Japanese submarine I-59 (which was later re designated I-159) under the command of Lieutenant Yoshimatsu and torpedoed. Rooseboom capsized and sank rapidly leaving one life boat (designed to hold 28) and 135 people in the water. 80 people were in the lifeboat and the rest clung to flotsam or floated in the sea. Two of these survivors were picked up 9 days later by the Dutch freighter Palopo. Until the end of the WWII they were assumed to be the only survivors.

The lifeboat.

Walter Gardiner Gibson (a corporal from the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders is the only known witness of the events that would occur on the lifeboat over the next 26 days. His tale was told to the British authorities after the war but was first heard publicly in court in Edinburgh in 1949 in order to confirm that Major Angus Macdonald was dead so that his estate could be settled.

According to Gibson, in and around the lifeboat were an estimated 135 survivors, many with injuries, including Gibson himself who was in the lifeboat due to those injuries. Among the survivors were the Captain M.C.A. Boon and the senior surviving British officer Brigadier Archie Paris (who had commanded the 15th Indian Infantry Brigade during the Battle of Malaya). There were also two other Argyll officers aboard the Rooseboom; Major Angus Macdonald, second in command of the Argylls and Captain Mike Blackwood. These two officers were chiefly responsible for holding up a Japanese tank column during the Battle of Bukit Timah. Paris, MacDonald, Blackwood and number of the other military passengers were among a selected few of the most proven fighters chosen to be evacuated instead of being lost to a POW camp.

By the time the boat had drifted for more than 1,000 miles, to ground on a coral reef less than 100 miles from Padang, Rooseboom 's starting point, only five of its 80 passengers remained alive, and one of those drowned in the surf while trying to land.

In Gibson's account the ordeal that followed the sinking showed the worst of human nature under some of the most extreme conditions. On the first night many of those in the water drowned or gave up. Some 20 men built a raft from flotsam and towed it behind the boat. The raft slowly sank and all 20 perished three days later. In the first few days discipline collapsed. Men and women went mad with thirst, some drinking sea water, which sent them into hallucinations. Many threw themselves overboard rather than face further suffering, and a gang of five renegade soldiers positioned themselves in the bows and at night systematically pushed the weaker survivors overboard to make the meagre rations go further.

In Gibson's account the ordeal that followed the sinking showed the worst of human nature under some of the most extreme conditions. On the first night many of those in the water drowned or gave up. Some 20 men built a raft from flotsam and towed it behind the boat. The raft slowly sank and all 20 perished three days later. In the first few days discipline collapsed. Men and women went mad with thirst, some drinking sea water, which sent them into hallucinations. Many threw themselves overboard rather than face further suffering, and a gang of five renegade soldiers positioned themselves in the bows and at night systematically pushed the weaker survivors overboard to make the meagre rations go further.

Gibson claims to have organized an attack on the renegades with a group of others who rushed them and pushed them en masse into the sea. Brigadier Paris died, hallucinating before he fell into his final coma. The Dutch captain was killed by one of his own engineers. Towards the end Gibson realized that all who remained alive were himself, another white man, a Chinese woman named Doris Lin and four Javanese seamen. That night the Javanese attacked the other white man, killed and then ate part of him. Later the oldest Javanese died.

The lifeboat fetched up on Sipora an island off Sumatra and only 100 miles from Padang where the Rooseboom started its journey 30 days earlier. One of the Javanese seaman drowned in the surf while the other two disappeared into the jungle and have never been found. After a period of being treated by some of the local population Doris Lin and Gibson were discovered by a Japanese patrol. Gibson was returned to Padang as a POW while Lin was shot as a spy soon afterwards.

Adrift for 26 Days in a Lifeboat by Walter Gibson

The Courier-Mail, Brisbane, Australia (1950)

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

The Last Chapter

Final Installment

Walter Gibson also wrote about this experience in The Boat (1952) and Highland Laddie (1954). He settled in Canada and died there on March 24, 2005 at age 90.

The lifeboat fetched up on Sipora an island off Sumatra and only 100 miles from Padang where the Rooseboom started its journey 30 days earlier. One of the Javanese seaman drowned in the surf while the other two disappeared into the jungle and have never been found. After a period of being treated by some of the local population Doris Lin and Gibson were discovered by a Japanese patrol. Gibson was returned to Padang as a POW while Lin was shot as a spy soon afterwards.

Adrift for 26 Days in a Lifeboat by Walter Gibson

The Courier-Mail, Brisbane, Australia (1950)

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

The Last Chapter

Final Installment

Walter Gibson also wrote about this experience in The Boat (1952) and Highland Laddie (1954). He settled in Canada and died there on March 24, 2005 at age 90.

Saturday, April 6, 2013

Struma ~ 23 February 1942

Found at www.israelsdocuments.blogspot.com.

The Turkish authorities refused to allow the ship's passengers to disembark, despite the worsening conditions on the ship. There was an acute shortage in food and drinking water, despite help provided by the Jewish community of Istanbul. The passengers suffered from cold, filth and hunger. All that time, a frantic negotiation took place between the Jewish Agency and the Joint Distribution Committee with the Turkish government and the British government (and the British Palestine government) trying to allow the passengers to land in Istanbul and reach Palestine. Both governments were resolved not to allow any of the Jews in the ship into Turkey or to Palestine. The British refused even to subtract the number of the Olim in the Struma from the overall number of Immigrants allowed under the limitations of the 1939 White Paper. At the same time, the British pressured the Turks to return the ship to Romania in order to block future immigration from the Balkans. Britain's High Commissioner in Palestine, Harold MacMichael, was especially adamant in his refusal to compromise on any offer of the Jewish Agency.

The sinking of MV Struma - February 1942

On February 24, 1942, a ship was sunk in the Black Sea, just off the entrance to the Bosphorus straits. On the same day, nine other ships were sunk in the Atlantic Ocean, in what is known today as "the Battle of the Atlantic" – the German U-boat war against shipping to and from Britain. Other ships were sunk in the Pacific Ocean – three days later came the dramatic battles of Java sea, Sunda Straits and the Second Java Sea (all Allied defeats). The ship sunk in the Black Sea, the MV Struma, wasn't carrying supplies or troops – it was carrying Jewish refugees, escaping the "Final solution," the extermination of the Jewish people in Europe. The sinking of the Struma is regarded as one of the greatest maritime disasters of World War II, and the largest one with only civilian casualties (the three other major disasters: the sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff, the Goya and the Armenia, also carried military personnel).

|

A photo of a ship believed to be The Struma (Wikipedia)

|

The Struma was a river boat operating in the Danube River, and was built in 1867. It was converted to a livestock ferry sometime in the 20th century. It was a rickety ship in bad technical condition which became even worse after an unreliable engine was installed. The ship was purchased by the New (Revisionist) Zionist party in Rumania in the purpose of ferrying a group of immigrants (Olim) from Romania to British-mandated Palestine. A group of 300 Rumanian Jews registered for the trip, but the numbers swelled after the rise of the Anti-Jewish laws and persecutions in Romania and the filtering news of the killing of Jews in Poland and the Soviet Union. (Here's a report written to the Jerusalem District commissioner, probably by Moshe Sharett, the head of the Political department of the Jewish agency.)

The ship left Constanta port in Romania on December 11,1941, en route to Istanbul. It was assisted by a tug boat – a sign of its bad mechanical condition. Its engine broke down several times during the journey, and a trip that should have taken 14 hours took three days.

|

A map of the Bosporus straits. The number 2 represents the

spot where the Struma was sunk (Wikipedia)

|

On February 23, 1942, after 10 weeks in Istanbul's harbor, the Turks had had enough. They forcibly towed the Struma outside of the harbor and into the Black Sea. Several hours later, in the early morning of February 24th, a Soviet submarine (later identified as the ShCh-213) launched a torpedo which blew the Struma out of the water. Her entire crew and all her passengers, save one, perished. The lone survivor, David Stoliar, was picked up by a Turkish fishing boat several hours later.

The sinking of the Struma caused a storm of protests and anger in the Jewish community in British mandated Palestine. In a letter to the chief secretary of the Palestine government, John Macpherson, Moshe Sharett blamed the British government for its discrimination against Jewish refugees while allowing the entrance of non-Jewish refugees without any limit, and demanded that Jewish refugees should be allowed to enter Palestine without limitation, since they were escaping persecution and murder. (The Israel State Archives used this letter in its publication Moshe Sharett – The Second Prime Minister, Selected Documents, 1894 – 1965.) The IZL – the National Military Organization (known as the "Irgun") underground published a "Wanted for Murder" poster with the picture of Macmichael on it (it tried to assassinate him in 1944) for his responsibility for the Struma disaster.

The Eichmann trial in 1961 revealed another side of the Struma disaster – the German side. In a letter to Eichmann's headquarters in Berlin, his representative in Romania, Richter, reported to him on his conversation with Mihai Antonescu, vice president and foreign minister of Romania, regarding the efforts of Jews to escape from Romania. Antonescu explained that he did not allow the Struma to leave Romania and her departure was approved by the head of the Siguranta, the Romanian secret police, who was sacked subsequently. The report notes that since the Turks were not willing to let the refugees enter Turkey, they would be sent back to Romania. (The letter shown here is a copy of the original letter in German. It's from the Israel's National Police Unit Bureau 06, which was responsible for preparing the police investigation, prior to the Eichmann trial in 1961.)

The Struma was another terrible chapter in efforts of Jews to escape from Europe during the Holocaust. It was another symbol of the helplessness and the trap in which the Jews of Europe found themselves. They could not escape their tormentors and pursuers and were not protected by the enemies of their enemies, which should have helped them, but instead sent them back to a certain death.

Wednesday, April 3, 2013

Vyner Brooke ~ 14 February 1942

Found at www.ww2australia.gov.au

"... It was lovely, it was Australia ...

I just wanted to howl ..." ~Sylvia Muir

On 23 October 1945, the hospital ship Manunda arrived in Fremantle. On the wharf were hundreds of waving and cheering people including Matron-in-Chief Annie Sage of the AANS. As the ship docked, people came on board carrying flowers and fruit. They had come to welcome home 24 Australian army nurses, women who had just spent three and a half years in Japanese captivity on the island of Sumatra and who, in February 1942, had survived the sinking of the Vyner Brooke.

Sisters Carrie Ashton, 2/13th Australian General Hospital

(AGH), and Mavis Hannah, 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station

(CCS), arrive to a homecoming celebration in Adelaide,

September 1945, after their three and a half years

of imprisonment in Sumatra.

The nurses were taken to recuperate in the Military Hospital at Hollywood in Perth. There they received more flowers than they had ever seen: ‘they came from every garden in Perth and kept on coming’. The matron at the hospital, Sister Eileen Joubert, had appealed over the local radio for flowers to brighten the wards for the nurses:

"The response was overwhelming. The large forecourt of the military hospital was covered in blooms, some of them brought hundreds of kilometres, others carried locally in wheelbarrows." [Michael McKernan in This War Never Ends, University of Queensland Press, 2001, p122]

[Left] A studio portrait of Staff Nurse

Vivian Bullwinkel in her AANS

service dress uniform.

The hand-coloured portrait

was made in May 1941.

The womens’ arrival in Australia was a combination of luck and perseverance. The Australian authorities had no idea where the Japanese had taken the nurses during the last months of the war. The search for them had started on 15 August 1945 but since no-one knew where they were, they missed out on the widespread emergency drops of food and medical supplies to the camps located around south-east Asia. By August 1945, they were starving.

Three and a half years earlier, after the sinking of the Vyner Brooke on 14 February 1942, 12 of the 65 Australian Army nurses on board were drowned or killed in the water. The rest struggled ashore on Banka Island, some having been in the sea for more than 60 hours. Japanese soldiers captured one group of 22 nurses, plus a civilian woman, ordered them into the sea and machine-gunned them. The only survivor, Sister Vivienne Bullwinkel, lay still in the shallow water until after the Japanese troops had gone. Days later, she was reunited with her surviving colleagues and interned at Muntok on Banka Island for two weeks before the group was transferred by ship to Palembang in Sumatra.

Japanese attempts to persuade the nurses to join a brothel were resisted by the women and they were eventually put into bungalows with Dutch women and children at the other end of the town. The conditions were dreadful with inadequate sanitation, mosquitoes, scarce food and, unlike many of the Dutch internees, the Australians had no resources with which to purchase supplements for their diet of low-grade rice and vegetables. In 1943 the women were moved again, this time to a desolate spot in the jungle where they eked out an existence in leaking bamboo huts with mud floors and trench toilets.

In October 1944, the Japanese moved their prisoners back to Muntok on Banka Island. Rations were worse than at Palembang and there were few medicines. Four of the nurses died in February and March 1945. Sister Pearl Mittleheuser died on 18 August 1945, three days after the Japanese surrender.

|

| the rescue |

Early in April 1945, the women and children were forced to take an appalling sea voyage back to Sumatra. They were packed into the holds of a small ‘bumping little launch’, many of them severely ill with malaria, dysentery and beri-beri. Others, some of them unconscious, were on stretchers and were carried by the ‘fittest’ of the women. Twenty-six hours later the women arrived at the wharf in Palembang. From there it was a train and then a truck trip to what was to be their final camp, Loebok Linggau in Sumatra. More than five hundred women and children were squeezed into the crowded and leaking ‘atap’ [bamboo and palm leaf] huts and all their water had to be carried from the creek. At first, the food supplied was an improvement, but after a month in the camp, the variety stopped and the diet was once again rice and sweet potatoes.

"We find we can eat most of the grass growing near the creek, also the young curling fronds of ferns. Curried fern with sweet potato is exactly like eating mushrooms!" [Betty Jeffrey, White Coolie, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1954, p162]

By now the women were in an appalling state but the Japanese still expected them to work in the camp.

After the Japanese surrender of 15 August 1945, Australian war correspondent Hayden Lennard began searching for the nurses. By following a number of leads from local villagers he eventually located them in their camp at Loebok Linggau. On 15 September, one month after the Japanese surrender the nurses were told they would be flown out of the camp.

Two nurses, Dora Gardam (left) and Mavis Hannah, staff members

of 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station (CCS) carrying the frame of

a bed in the hospital grounds in Malaya in 1941. Sister Gardam

died on Banka Island in the Netherlands East Indies on 4 April 1945

as a POW. Sister Hannah was the only member of 2/4th

CSS to survive the sinking and her captivity.

At 6.00 am the next morning, sixty women from the camp, including the Australian sisters, were driven in open trucks to the railway station. It took them nearly 3 hours to travel the 12 miles. At the station they were met by Hayden Lennard and a RAAF pilot, Flying Officer Brown, who had been landed at the Lahat aerodrome to collect them. The two men accompanied the women on the train to Lahat where they waited for their aircraft to arrive from Singapore. Nearly four hours later they watched it land. Out stepped the Matron-in-Chief of the AANS, Colonel Annie Sage with Major Harry Windsor and Sister Jean Floyd, one of their colleagues from the 2/10th AGH, who had managed to escape safely from Singapore. Expecting to recover many more of the nurses, Colonel Sage looked around at the small, emaciated group and asked: "But where are the rest of you?"

The Australian Army doctor who travelled with the rescue team, Harry Windsor, was so outraged by the appearance of the surviving nurses and the other prisoners at the camp that he recommended, officially, that the guards, the Kempei Tai [military police] and all of the those Japanese involved in their treatment,

"Be forthwith slowly and painfully butchered." [Report of Dr Harry M Windsor, Major, 2/14th AGH, 19 September 1945. NAA MP742/1 Item 336/1/1289]

Historian Michael McKernan, who discovered Dr Windsor’s report in the Australian Archives in Melbourne, wrote of his reaction to the doctor’s words:

"The savagery of this statement would leap at any researcher however drowsy in the hushed quiet of an archival reading room. The words were more dramatic for me as I had known Harry Windsor in his later life; his son is one of my closest friends. The passion, the grinding anger, is entirely at odds with everything I knew of this man or had been told of him. Those few words of brutal and savage retribution, ‘slowly and painfully butchered’, I have no doubt were precisely what Harry Windsor wanted to order for these Japanese whom he now despised for what they had done." [Michael McKernan, This war never ends, UQP, St Lucia, 2001, p 73]

[Right] Sisters Betty Jeffrey and Jean Greer recovering from malnutrition in hospital in Singapore. Sister Jeffrey

weighed just 30 kilograms and

was suffering from tuberculosis

when she was liberated.

Only 30 passengers could be carried on the aircraft so the Army nurses left that afternoon. Matron Sage and Sister Floyd remained in Lahat to look after the civilian women who were to fly out the next morning. The nurses’ aircraft landed in Singapore at dusk that evening and they were taken straight to the Australian hospital at St Patrick’s College. There they learnt to sleep on proper beds with sheets, to enjoy proper food and for the next few weeks they were ‘fattened up’.

On 4 October 1945, after enduring three years and seven months as prisoners of war, the 24 sisters sailed for Fremantle, Australia.

Nurse survivors of the Vyner Brooke

When the fighting on the Malayan peninsula reached a climax in early 1942, and both the probability of a retreat to Singapore Island and its risks became apparent, the problem of returning the seriously ill and wounded, as well as the members of the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS), to Australia became urgent. Tragically, no evacuation by hospital ship was made while there was still time.

On 10 February 1942, six members of the AANS embarked on the Wah Sui with 120 sick and wounded soldiers of the Australian Imperial Force. On 11 February, 59 nurses embarked on the Empire Star, and another 65 sisters and physiotherapists sailed on the Vyner Brooke on 12 February. On 14 February, while heading for Sumatra via Banka Strait, the Vyner Brooke was sunk by Japanese bombers. Sister Vivian Bullwinkel was with a group of 22 survivors on Banka Island when a Japanese patrol arrived and ordered the women in the group to walk into the sea. They were machine-gunned from behind. All except Sister Bullwinkel were killed.

Of the 65 servicewomen who embarked on the Vyner Brooke, only 24, including Vivian Bullwinkel and Betty Jeffrey, returned to Australia. Of the 32 taken prisoner of war, eight died in captivity.

On 10 February 1942, six members of the AANS embarked on the Wah Sui with 120 sick and wounded soldiers of the Australian Imperial Force. On 11 February, 59 nurses embarked on the Empire Star, and another 65 sisters and physiotherapists sailed on the Vyner Brooke on 12 February. On 14 February, while heading for Sumatra via Banka Strait, the Vyner Brooke was sunk by Japanese bombers. Sister Vivian Bullwinkel was with a group of 22 survivors on Banka Island when a Japanese patrol arrived and ordered the women in the group to walk into the sea. They were machine-gunned from behind. All except Sister Bullwinkel were killed.

[Right] Group portrait of Australian Army

Nursing Service (AANS) nurses, who were

former prisoners of war, aboard the hospital ship

Manunda on its arrival. Matron Vivian Bullwinkel

is third from the right holding flowers.

Nursing Service (AANS) nurses, who were

former prisoners of war, aboard the hospital ship

Manunda on its arrival. Matron Vivian Bullwinkel

is third from the right holding flowers.

Of the 65 servicewomen who embarked on the Vyner Brooke, only 24, including Vivian Bullwinkel and Betty Jeffrey, returned to Australia. Of the 32 taken prisoner of war, eight died in captivity.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)