Found at www.australianyarns.wordpress.com.

Torpedoed Australian Hospital Ship

“AHS Centaur” Found

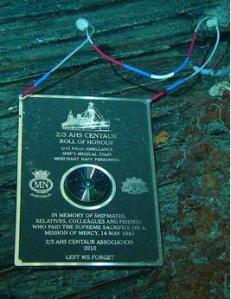

After lying undetected for 66 years on the ocean floor as a watery grave for 268 souls, the AHS Centaur has finally been found.

Few disasters of the Second World War (1939-45) moved Australians as much as the sinking of the Australian Hospital Ship (AHS) Centaur. At the time, each single aspect of this tragedy would have been enough to cause national aghast, but taken collectively, they caused a great outpouring of emotion that still makes us reflect with sadness, some 66 years later.The Centaur sinking involved all the horror of 268 souls from a ship’s company of 322 being lost; an attack on Australians taking place just 30 miles from where they lived; an attack on a hospital ship that was supposedly protected under the Hague Convention; an outcome of a sea grave for so many that provided no real closure for the loved one left behind; the seemingly callous murder of those compassionate and devoted nurses and doctors and the possibility of our military leaders making Centaur a ‘sitting duck’ legitimate target by using it to transport weapons and army personnel.

Still in the midst of a tragedy so great there remains the heroic, compassionate and generous acts. So, the discovery of the Centaur’s final resting place in December 2009, with its entombed souls, does provide some closure for the relatives and friends of the missing. For the rest of us, it is a chance to re-examine who was truly responsible for this tragedy and yet also to remind us of the nobility of the human spirit that through courage and duty can outshine even the repulsiveness of war.

Here is the Centaur story …

Centaur lost in 1943 … found in 2009

For 66 years the Australian Hospital Ship (AHS) Centaur, has been lost in a watery grave, now found lying 2,059m below the surface of the sparkling blue Pacific Ocean, some 30 nautical miles due east of the southern tip of Moreton Island. It was found within one nautical mile that the much maligned Centaur navigator Gordon Rippon said it would be.

This was to be her final resting place after being torpedoed at 0410hrs on the 14 May 1943 by a Japanese submarine. Sharing that graveyard are the ship’s 268 nurses, doctors, field ambulance officers and crew who lost their lives on that fateful night.

On the 20 December 2009, the Centaur’s search director, David Mearns, on board the Defence Maritime Services support vessel ‘Seahorse Spirit’ was able to advise the Australian and Queensland governments that he had found the Centaur. Having jointly committed $4 million to the search, the officers from the Commonwealth Department of Defence and the Queensland Department of Premier and Cabinet also provided oversight and technical assistance to the project.

|

Centaur, by Sandy Freeleagus (Image 11)

|

Now that the Centaur has been found, the enduring and unanswered questions about who was responsible for this tragedy may well be answered. The wartime explanation of a ruthless Japanese submarine commander acting alone and callously ordering the launch of the torpedo at an unarmed and unescorted hospital ship is the favored line. However, this story is today challenged by growing evidence that military commanders at the time loaded on guns, munitions and soldiers making the Centaur a legitimate wartime target. If the second explanation proves true then who is most responsible for the tragedy of the Centaur.

Leaving responsibility aside, this was a real tragedy for a nation, the 268 people who lost their lives, the 65 survivors and all the families involved.

In 2009, only 3 of the 65 AHS Centaur survivors are alive to witness the find. They are Martin Pash the ship steward, are Bob Westwood in cabin boy who was in the care of Ellen Savage after the sinking and Seaman Matt Morris. Of them all, only Martin Pash remained in good health. Let’s first deal first with their stories ⇢

Disaster struck at 0410 hrs for AHS Centaur

|

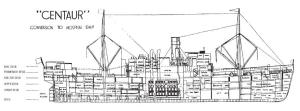

Centaur (Image 8)

|

Centaur began her 2nd voyage from Sydney to New Guinea, at 10:44 am of 12 May 1943. She was unarmed and unescorted and declared as carrying no combat troops.

On board were 332 persons that comprised of;

- 75 Merchant Navy crew

- 12 nurses of the Australian Army Nursing Service most of whom were transferred from the hospital ship Oranje.

- 50 other medical staff, including 19 doctors. There were 8 Officers with some of the staff coming from the 113th Australian Army General Hospital (RGH Concord)

- 1 Red Cross representative – W.F.D Clark

- 1 ship’s pilot ⇒ 67 year old Capt. R. M. Salt, a Torres Strait pilot, of Sydney

- 149 men of the 2/12th Field Ambulance

- 44 attached personnel heading for a tour in Papua New Guinea.

- 0 patients

The three Companies of the 2/12 Field ambulance and attached personnel were declared passengers, travelling to New Guinea to set up field medical units there. The 2/12th, led by their Commanding Officer LT. Col Leslie McDonald Outridge, had marched on to the wharf at No1 Darling Harbour Sydney ready to board the Centaur.

Centaur was to be following a course into an area that had previously seen the “Kalingo”, the “Lydia M Childs”, the “Wollongbar”, the “Fingal” and the“Limerick” sunk in the previous five months. It was a known unprotected shipping lane at the time that was active with Japanese submarines operating from a forward base in occupied Guam, and attacking at will.

On the third night of the trip the Centaur was placed about 24 miles E.N.E off Point Lookout Stradbroke Island as she continued to head for the first port of call, Cairns. She traveled as a non-combatant vessel, fully lit, and displaying the markings of the Red Cross that had been freshly painted on only two days prior to leaving Sydney. Prior to being commissioned as a hospital ship (AHS47) on the 12 March 1943 the Centaur served as a cargo ship.

In fine and clear weather with good visibility at 0410 hrs, she was struck by a torpedo from the Japanese submarine “I-177″on the port side near her oil bunkers just behind No. 2 Hatch. A tremendous explosion rocked the ship, the bridge superstructure collapsed and the funnel crashed onto the deck. Everything was covered with burning oil and a fire quickly began to roar across the ship.

At that time of night, most of the personnel were asleep and below decks. The explosion caused the ship to list precarious to port and with the sea flooding in through the gaping hole in her side, most of the people below deck became trapped in their bunks and unable to escape.

There was no chance to send out a wireless S.O.S. and no time to launch the lifeboats. In fact, most of the life boats were destroyed in the explosion. The ship capsized and sank within three minutes so many victims that did not die below decks were sucked down as the ship plunged to its watery grave bow first.

| Owner: | Alfred Holt Ocean Steamship Company (The Blue Funnel Line), Liverpool | Builder: | Scotts Shipbuilding and Engineering Co., Greenock |

| Beam: | 48.2 ft. (14.7 metres) | Gross tonnage: | 3,222 |

| Depth: | 21,5 ft. (6.6 metres) | Net tonnage: | 1901 |

| Engine: | 4-stroke, 6-cylinder, oil-fired, blast-injected Burmeister & Wain | Decks: | 2 tween decks and upper ‘shade’ deck |

| Holds/Hatches: | 4 | Grain space: | 240,000 cu ft (6,800 cu metres) |

| Bale space: | 220,000 cu ft (6,200 cu metres) | Livestock capacity: | 72 |

| Passenger capacity: | 72 | Official number: | 147275 |

| Year Built: | 1924 | Length: | 315.7 ft.(96 metres) |

|

The 34 hours before rescue

Of the 332 persons on board, less than a hundred were not taken with the ship as it plunged to the depths, but of those remaining only 64 managed to survive the burns, the ingested oil, the circling sharks and the 34 hours of hell waiting to be rescued. Because the Centaur was maintaining radio silence, all rescue attempts were delayed.

|

USS Mugford (Image 12)

|

After the sinking began the second stage of the horrific experience – trying to survive in the ocean until rescue came.

The hundred or so survivors finding themselves in the water once the Centaur sank were covered in thick oil. Many with broken limbs, burns or internal injuries, now tried to find wreckage to support them. Some survivors clinging to wreckage were taken by sharks.

At one point preceding the dawn on the second day, one group of survivors including Ronald (Ronnie) Moate, thought they saw a ship.They sent up two flares, but then, to the horror of the survivors, realised it was a Japanese submarine. “We just lay down and hoped they had not seen our flares,” added Moate. “The submarine remained on the surface for about half an hour and then disappeared”. The survivors had stayed low waiting for the expected machine-gunning to start – but the submarine soon submerged obviously just recharging its batteries on the surface.

George McGrath, a driver attached to the 2.12th Field Ambulance explained it like this:

“It was about midnight when we were startled by the sudden roar of engines, prompting Banks to say, ‘It’s a submarine, up to charge its batteries.’ I was able to make out the outline of a vessel showing a red light. One of the survivors, thinking it might be a friendly submarine, lit a flare which Banks immediately extinguished in the water. The sub crash dived, much to our relief, as Banks expected to see a search light and to be machine gunned. Nothing more was heard or seen of the submarine. It was bitterly cold…”

On the morning of the first day two large rafts joined their party, which had thus increased to seven, with a total of 31 persons aboard. Only one raft carried provisions, which gave them 2000 milk tablets, 7lbs. of prunes, 2lbs. of chocolates, a tin of raisins and two gallons of water. To guard against a delayed rescue, food and water were rationed, said Moate.

Radiographer Sgt. Dick Metcalf, one the Centaur’s survivors gives the following account:

"I am sitting, hunched on a carley float, huddled against a shivering companion.

“What was it?” says a voice.

“Bloody Japs, a torpedo,” says someone.

Not a bloody hope. God knows how I got out!

When dawn breaks there are heavy clouds and we look about. Another carley float is about 50 yards (50m) away with more figures, so we paddle with broken boards to get together. Someone throws a rope and we tie about 20 feet (6m) apart. In the daylight, I recognise Nell Savage, the only nurse to survive from the 12 on the ship. Nell is looking after the 15-year-old ship’s cabin boy.

My mate next to me is naked and shivering so I give him my jacket. We’re not cold, just all very shocked. Many are injured and burned, one has large pieces of wood through his arms and Nell says: “Don’t try to take them out, or he might bleed badly.”

So we sit through the day – still thick overcast. We hear planes but all are above the clouds, and finally night falls. Morning, still overcast, and we realise we have visitors. Sharks – as far down as we can see more and more! One circles each raft and rubs his back on the rope between; no wonder we’ve lost nearly 300 mates.

Later on that day, another plane, but this time, nearer and nearer then suddenly, right before us one of our Avro Ansons comes out of the clouds and circles us. Everyone is yelling and waving and the plane drops a green flare then heads off to the east where we can now see the superstructure of a ship.

Then, wonders, a destroyer heads straight for us! The plane stays over the other ship!

The destroyer USS Mugford comes to a stop right beside our rafts and the sailors drag us aboard as quickly as possible up cargo nets.

|

Centaur survivors (Image 14)

|

The USS “Mugford” had been escorting the British Steamer “Sussex” on a voyage across the Tasman Sea. The destroyer was directed to the scene by an RAAF Avro Anson search aircraft from 71 Squadron RAAF based at Lowood Airfield. The ship’s Commander, showed great courage when he ordered his vessel to heave to, in waters threatened by enemy submarines.

“By midday on the second day we could have drunk the ocean dry. The rescue ship came two or three hours afterwards.” Ronald Moate said that many members of the party were naked. During the 34 hours they were afloat his party sighted seven planes and two ships but apparently they were not sighted until the last plane flew over, about 3 o’clook on the second day. Most of the survivors were able to reach rafts, but some were rescued from planks and spars. Four men remained on the chart house roof for 36 hours.

“Don’t let them tell you that sharks won’t come through oil,” declared Francis Davidson, butcher, of Balmain. “The sharks were plentiful and were not afraid to swim through oil. They were hungry, too,” he said.“One of our party threw a coloured tin at them and a big shark snapped the bottom right off.”

|

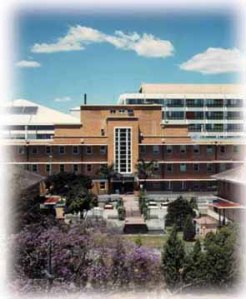

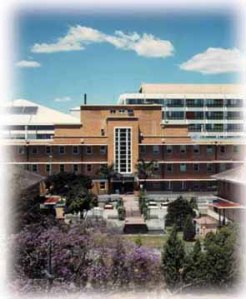

Greenslopes Hospital (Image 13)

|

Alan Dickson had this to say about the American sailors from the USS Mugford:

“There was a fellow, he wouldn’t have been any more than about 5-foot-3, but he was as wide as he was long. Some of our fellows were getting a bit weak, you know, and they’d try to get over to a net to get up, and they’d fall in the water, and like that, he’d be in amongst the sharks, he’d haul the survivors on his shoulder and climb up. There were three other sailors there with machine guns shooting at the sharks.”

Eventually all remaining survivors were taken ashore in Brisbane for treatment at 112AGH Greenslopes Hospital.

So, of the 322 personnel that left Sydney on the 12 May 1943 only 65 survived. These included:

- 29 of the ships crew of 75 that boarded. Many were on duty at the time. Those off duty were quartered at the front and rear ends, and below decks.

- 14 of the 2/12th Field Ambulance of the 149 that boarded. These were quartered in the middle hospital ward area.

- 19 army medical personnel of the 89 that boarded. These were quartered in the middle hospital ward area.

- 1 nurse Sister (Nell) Savage of the 12 the boarded. The medical staff were quartered at the ends of the ship, and between decks.

- 1 doctor of the 19 that boarded. The medical staff were quartered at the ends of the ship, and between decks.

- and the ship’s pilot – Richard Mumford Salt.

VIDEO

The remarkable Sister Elenor Savage

Already singled out for great praise by all who saw her calm courage in the ordeal through which she passed, is Sister Eleanor (Ellen) ‘Nell’ Savage of Quirindi, NSW, who with three broken ribs, helped a 15 year old youth, Bob Westwood, to swim to a raft and later shared with him a great-coat that had been found for her.

Sister Savage, who made no mention of her injuries all the time she went on the raft, was in her cabin when the alarm was given.

She was awakened by a cry of “On deck, Savage!” from her best friend, Sister King, who was in the next cabin.

With her Rosary beads in one hand and a life preserver in the other. Sister Savage, a pretty brunette, who now has numerous lacerations, a black eye and a badly puffed face, in addition to broken ribs, ran with two companions, including Sister King, to the deck, where she became separated from the others.

By this time the Centaur was on fire and, scrambling over the deck-house roof with the ship’s cabin boy, Bob Westwood, who was badly burned, she reached the side and they jumped into the water. They swam through oil which surrounded the stricken vessel but which had not caught fire. She and Westwood managed to reach a raft, where a medical officer, Col.Outrldge, treated the youth. “My first thought was to say a prayer when we were saved and that our friends might be saved, too, for no one could say in the turmoil of the night who had escaped and who had gone down,” declared Sister Savage when relating her experience.

Col. Outridge did a lot to keep the morale of the people by his own calm and splendid competence,” she added. While on the raft, Sister Savage, despite her injuries, managed to say a prayer for a man who died from burns and was buried at sea. She lost most of her clothes while in the water and two men on the raft gave her a pair of trousers and an overcoat.

Paying tribute to Sister Savage, Col. Outridge, speaking from a hospital bed in which he was lying with his head and hands swathed in bandages as a result of severe burns, said that the nurse had injured her ribs when she jumped from the burning ship and must have been in great pain the whole time.

|

Sister Ellen Savage (Image 2)

|

“Like most of those on the raft, she did not say she was hurt,” headed. “She did an admirable job with food and water and in looking after the boy, Westwood. She made him her special charge and refused to allow anyone to part him from her.”

“She behaved magnificently. She is a wonderful woman,” declared Fireman William Mcintosh, of Glasgow, who, with two other men, managed to pull Sister Savage on to the raft."

Sister Savage was the only nurse to survive and for her courage and inspiring behaviour during this period Sister Savage was awarded the George Medal.

After the war, Ellen Savage gained a Florence Nightingale scholarship and attended the Royal College of Nursing in London to study nursing administration. She eventually became Matron of the Rankin Park Chest Hospital until her retirement in 1967. She died on 14 May 1985 which ironically was the 42nd anniversary of the centaur’s sinking. She was 72 years old.

|

George Medal Sister Ellen Savage (Image 10)

|

The political response – ‘Avenge the Nurses’

“Disregarding all standards of human decency and with complete contempt for all provisions of international law, a Japanese submarine, 40 miles east of Brisbane early on Friday morning, sank the Australian hospital ship Centaur of 3000 tons.” … and so read the headlines of The Canberra Times on Wednesday 19 May 1943.

Few disasters during the Second World War touched Australians as deeply as the loss of the Centaur. This attack (the worst Merchant Ship tragedy on the Australian coast during WW2) on a clearly marked and illuminated hospital ship was taken as further evidence that Australia faced a brutal and uncompromising enemy. The Centaur then as it does today, came to symbolize the courage of Australian women in war and continually reminds us of all Australians who served in war and have no graves but the sea.

In 1943 Australia was in fear of being invaded by Japanese forces. The Kokoda campaign which saw the Japanese army on our door step in Port Moresby, had just ended late in the previous year. The threat was real even if some sections of the Australian community remained complacent. Moreover there was a growing fear that the enemy was ruthless and playing outside the rules of decency in war (if that were possible).

Stories were trickling through about cold blooded beheading of hundreds of Australians from the Laha airfield in February 1943 and the execution of several airmen from the Doolittle Raid announced by President Roosevelt in April 1943. Now they were sinking our hospital ships inside of our waters.

If there was any complacency towards the Japanese threat prior to the Centaur’s sinking it was totally eradicated afterwards … and the politicians and military leaders of the time took full advantage of the atrocity to make it so.

The Canberra Times article goes on to say …

“Mr. Curtin said that news of the sinking would come as a profound shock to the Australian people. The attack bore all the marks of wantonness and, deliberation. Not only would it stir the people into a more acute realisation of the type of enemy against whom we, were fighting, but he was confident also that this deed would shock the conscience of the whole civilised world and demonstrate to all who might have had any lingering doubts, the un scrupulous and barbarous methods by which the Japanese conducted.”

General MacArthur, Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area and commander of the Australian military, commenting on the sinking at the time, and said:

“I cannot express the revulsion I feel at this unnecessary act of cruelty. Its limitless savagery represents a continuation of a calculated attempt to create a sense of trepidation through the practice of horrors designed to shock normal sensibilities. “The brutal excesses of the Philippine campaign, the, execution of our captured airmen and the barbarity of Papua are all of a pattern. The enemy, does not understand, apparently he cannot understand that our invincible strength is not so much of the body as of,the soul, and it rises with adversity. The Red Cross will not falter with this foul blow. Its Light of Mercy will, but shine brighter on our way to inevitable victory.”

|

(Image 6)

|

The opposition leader of the time. Mr Fadden, was equally scathing of the attack and its spoke of the impact on the Australian psyche.

“Australians will share with members of the Opposition a feeling of horror regarding the dastardly act perpetrated by the enemy so close to Australian shores, declared the Leader of the Opposition (Mr. Fadden).

Continuing, Mr. Fadden added that … the fact that the sinking occurred so close to Australia should bring home with considerable force to those com placent members of the community and also the irresponsible industrialists the danger with which Australia was threatened.”

News of the attack not only made front page in Australia it resonated around the world. The story was carried on the front pages of The Times of London, The New York Times, and the Montreal Gazette

The initial public reaction to the attack on Centaur was one of outrage, and an example of Japanese “limitless savagery”. Politicians leveraged the public rage to fuel the war effort, and Centaur became a symbol of Australia’s determination to defeat what appeared to be a brutal and uncompromising enemy. The poster here produced by the Australian Government depicting the Centaur’s sinking, which called for Australians to “Avenge the Nurses” – even though only 11 of the casualties of the 268 were in fact nurses.

The Hall of Memories in the Australian War Memorial depicts on of the four pillars a mural to Women Services. Part of the mural shows ‘engulfing waves of the sea into which sinks the “sea-centaur”, symbol of that war tragedy in which the hospital ship Centaur was sunk and all but one of her nurses lost their lives.’

|

Women Services AWM Centaur nurses (Image 16)

|

The unanswered questions of AHS Centaur?

Where is the truth?⇛ Did Australian military commanders knowing breach the Geneva and Hague Conventions by loading soldiers, weapons and munitions onto the Centaur making it a legitimate wartime target?

or⇛ Did the Japanese submarine commander Lieutenant Nakagawa callously sink an unarmed clearly visible and marked hospital ship?

For 66 years these questions have remained and just maybe some of them will be answered with an examination of the wreak of the AHS Centaur found on the 20 December 2009.

- Why did the Japanese fire at a vessel clearly marked as a hospital ship? The Japanese government had been notified of the ship’s status on February 5, 1943 and 8 months previously, Japanese ships in Milne Bay in Papua New Guinea had trained their spotlights on the hospital ship Manunda, which was similarly marked but they did not fire on it. Did the Japanese believe that the Centaur was carrying weapons and army personnel making it a legitimate wartime target?

- Why did the waterside workers in Sydney stop work over the loading of rifles and ammunition before the Centaur sailed on the 12 May 1943? Did they believe that it breached the Geneva and Hague Conventions which governed the protect of hospital ships?

- Did the Japanese spy ring that operated out of Sydney at the time, believe that the military disciplined 2/12th Field Ambulance Regiment embarking the Centaur in jungle greens, were actually commandos? Only a regiment patch on their uniforms separate the look of ambulance personnel from regular soldiers.

- Why were the known rifles that were carried by 2/12 ambulance personnel onto the Centaur ordered to be placed between the matrices in one of the cargo bays? What was in the other three cargo bays?

- Why was the Centaur so close to the Brisbane coastline in 1943 being just 30 miles off Moreton Island and not 110 miles offshore as ordered?

- Who was Colonel English? He was listed as being picked up by the USS Mugford but there no record of him boarding or being listed in subsequent official survivor listings? Were there commandos on board? Was Colonel English their commander?

- In 1979 the Japanese government acknowledged that Lieutenant Hajime Nakagawa commander of the submarine 1-177 was responsible for the sinking of the Centaur but at a War Crimes trial in 1948 for other acts neither the Japanese or Australian governments pushed for him to be found guilty of the Centaur attack. Australian authorities had already declared it a war crime in a 1944 investigation, yet did not press for charges against the commander in 1948. Would the evidence have vindicated the decision that the Centaur was a legitimate war time target?

- Why did the submarine Captain want to sink an empty ship? With less than 10 torpedoes and a plethora of ‘rich pickings’ sailing those sea lanes, why sink a ship of no strategic war time value? How the Centaur sat in the water would have revealed to the submarine commander wether she was loaded or not.

- What was the second explosion that the survivors spoke about? Exploding ammunition? Why did the hole in the hull blow outwards with the metal protruding from the ship as spoken about but never questioned in the survivor evidence given at the investigation in 1944.

- Is there a telex that reads ‘SS Centaur to proceed to Port Kembla to load Owen Guns 7th May 1943, sail same day to Sydney to load 9mm Ammunition. Depart Sydney 12th May 1943 dated April 1943.” We do know that 2000 pound (900kg) of ironstone from Port Kembla was loaded into the cargo holds of Centaur as ballast. There are questions about the value of 0.9 tonne ballast making much difference in a 3,330 tonne ship. Was ‘ironstone’ actually a code for ‘Owen Guns”?

- Why was the military command so keen to keep news of the Centaur sinking from the public? Is there a secret file on the Centaur that is not to be opened until 100 years after the event as one researcher claims?

- Is it true that in August 1988 a member of the 2/15th Australian Field Company (Engineers) told a magazine reporter that he had helped load ammunition on the Centaur? He said soldiers worked through the night loading the ship ‘almost to the gunnels’ with cases of ammunition, rifles and machine gun.

- Why would one of Australia’s most respected historians, G. Blainey, write the foreword on the book that questions the innocence of the Centaur. (Milligan, C. and Foley, J. Australian Hospital Ship Centaur: The Myth of Immunity)

Peter Baskerville was born in Australia and has lived the vast majority of his life in the country of his birth apart from a few years in Fiji and New Zealand pursuing business interests.

Despite imbibing the inherent non-nationalistic attitude that naturally comes with being an Aussie, we just can’t help loving this place called Australia – its vast open spaces, its pristine beaches, its unspoiled outback landscapes, its melting pot of immigrants, its ancient heritage of the First Australians, its Anzac spirit, it mateship creed, it hard working, positive yet carefree attitude to life … yes, and even its perils, dangers and strife – we love it all. It is a long way to come, but I’m sure you will find it well worth the visit, even better, come join us … the people of the land ‘down-under’.

AUSTRALIAN HOSPITAL SHIP CENTAUR

The Myth of Immunity.

Christopher Milligan and John C.H. Foley.

‘Jap sub sinks hospital ship!’ screamed the world’s press in May 1943. The unarmed and brilliantly lit ship was suppoosedly immune from attack, but down she went to a Japanese torpedo with the loss of 268 of the complement of 332. The death toll was the highest of any merchant vessel sunk by submarine in the Pacific during World War 2. Fifty years later however the innocence of the ship has been questioned – was she carry munitions? This is a remarkable book, exceptionally well researched with a forward by Professor Geoffrey Blainey. It asks many questions, and resolves a few. Great reading.

Click HERE for list of those who died and survived.